FRENCH rule and TENSIONS in the colony: 1750-1784

1750s

Free blacks and mulattoes, which emerge as a distinct class apart from colonialists and enslaved Africans, begin to amass wealth and power. "In fact, the free blacks owned one-third of the plantation property and one-quarter of the slaves in Saint Domingue, though they could not hold public office or practice many professions (medicine, for example)." (CHNM)

“These men are beginning to fill the colony and it is of the greatest perversion to see them, their numbers continually increasing amongst the whites, with fortunes often greater than those of the whites . . . Their strict frugality prompting them to place their profits in the bank every year, they accumulate huge capital sums and become arrogant because they are rich, and their arrogance increases in proportion to their wealth. They bid on properties that are for sale in every district and cause their prices to reach such astronomical heights that the whites who have not so much wealth are unable to buy, or else ruin themselves if they do persist. In this manner, in many districts the best land is owned by the half-castes. . . These coloreds imitate the style of the whites and try to wipe out all memory of their original state.”

— Colonial administrators writing to the Ministry of the Marine

Following a period of military victories and prestige in the 1740s, Louis XV's reign enters "one of its more typical periods of failure and discord, [and] a new flood of freedom suits hit the courts, and once again blacks began winning every case, either outright or on appeal. Abolitionists seek to establish that "No one is [a] slave in France." (Reiss, pp. 65-66)

1756

The town of Jérémie is officially founded in 1756 "and would grow in importance as the parish rapidly expanded in the 1770s and '80s." (Reiss, p. 36)

1756

The Seven Years' War begins. During the war, an English embargo "wreaked havoc on colonial shipping" and plantation owners lost thousands of livres' worth of cane to spoilage and the inability to export product (Reiss, p. 48).

1757

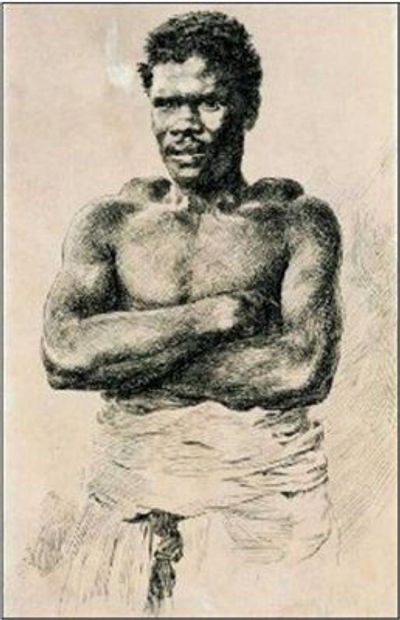

The Makandal Conspiracy.

François Makandal (alternately spelled "Mackandal" or "Macandal"), a maroon leader, conspires to poison all the whites in the North in a plot intended to spread to “all corners of the colony.” Across the North, Makandal’s vast network of collaborators – mostly trusted domestics – begin poisoning their masters' households, including other slaves who can’t be trusted. The whites search frantically for the cause of the illnesses and deaths. After an interrogated female slave betrays the rebel leader, the planters launch a massive manhunt and Makandal is eventually captured.

In March 1758, Makandal is executed. Colonists burn Makandal at the stake in the middle of the square in Le Cap. Owners bring their slaves and force them to watch. Despite witnessing his death, many slaves insist in Makandal’s immortality and he becomes a major inspirational figure for the slaves during the revolution.

Image: "François Mackandal." Link.

A Note on the Maroons

"The word marron derived from the Spanish cimarrón—"wild, untamed"—[was] first used to describe cattle that turned feral after getting away from Columbus's men shortly after they landed." (Reiss, p. 34)

Maroons were fugitive slaves who often fled into the mountains and lived in small bands while eluding capture. This phenomenon, called “marronage,” was crucial to the fight for Haiti’s independence. Maroons were some of the revolution’s most powerful figures, responsible for organizing attacks and uniting disparate groups even when their leaders deserted their cause and joined the colonists. Colonists ultimately fail to repel maroons' guerilla warfare tactics.

“Marronage, or the desertion of the black slaves in our colonies since they were founded, has always been regarded as one of the possible causes of [the colonies’] destruction . . . The minister should be informed that there are inaccessible or reputedly inaccessible areas in different sections of our colony which serve as retreat and shelter for maroons; it is in the mountains and in the forests that these tribes of slaves establish themselves and multiply, invading the plains from time to time, spreading alarm and always causing great damage to the inhabitants.”

— From a 1775 memoir, on the state of maroons in Saint Domingue

“The slave . . . inconstant by nature and capable of comparing his present state with that to which he aspires, is incessantly inclined toward marronage. It is his ability to think, and not the instinct of domestic animals who flee a cruel master in hope of bettering their condition, that compels him to flee. That which appears to offer him a happier state, that which facilitates his inconstance, is the path which he will embrace.”

— From the 1767 register of the Upper Council of Le Cap

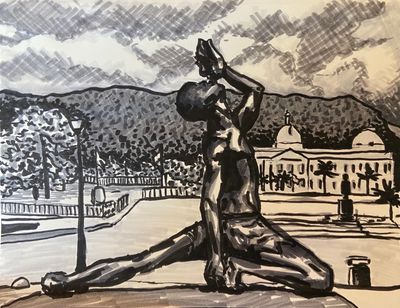

Image: Nèg Mawon statue, Kona Shen, ink brush pens on paper, 2022.

1763

The Seven Year War in Europe ends, and the Treaty of Paris is signed by Britain, France, Spain and Native Americans in Europe and the North American colony.

By this point, Saint-Domingue accounts for two-thirds of France's overseas trade. "It was the world's largest sugar exporter and produced more of the valuable white powder than all the British West Indian colonies combined. [...] When the British, after winning the Seven Years' War, chose to keep the great swath of France's North American colonies and instead return its two small sugar islands, Guadeloupe and Martinique, they unwittingly did their archrival a favor." (Reiss, p. 28) In retaining Saint-Domingue and the other West Indians islands, "The French would simply need to double down on sugar and slavery." (Reiss, p. 68)

The colonists increasingly resent France’s hold on their production, which prevents them from profitable trading with other countries. Colonists begin seeking greater administrative control of local affairs and the planters’ autonomy movement begin to gain momentum.

Image: Siege of Kolberg (1761). Link.

1763-1768

Affranchis, primarily composed of free mulattoes, threaten the colony's power structure as they become influential landowners in the colony. Whites seek to control the affranchis as their population grows along with their wealth and power.

Legislation designed to frustrate their ambitions and prevent assimilation with whites forbids the affranchis to hold public office, practice privileged trades (such as law or medicine), assemble in public after 9pm, sit with or dress like whites, gamble, travel, or enter France. These offenses are ruled punishable with fines, imprisonment, chain gang duty, loss of freedom, and amputation.

Despite these restrictions, affranchis are still obliged to compulsory military duty between the ages of 15 and 45. Furthermore, they are still allowed to lend money, a service which the colonists are becoming increasingly reliant on. During the 18th century the credit provided by the affranchis is critical to Saint Domingue’s growing size and wealth.

May 1771

Louis XV issues Instructions to Administrators, which outlines new restrictions against blacks and mulattoes. The Instructions elaborate on the Code Noir of 1685 and mulattoes find that they are stripped of many of their freedoms and privileges in the colony.

1773

Over 800,000 enslaved Africans are brought to Saint Domingue from 1680 to 1776. Over a third of them die within their first few years in the colony. People imported during this time are primarily from the kingdoms of the Congo and Angola. However, by this point the scope of the Atlantic slave trade has expanded so considerably that some slaves are brought from as far away as Mozambique, on the southeastern coast of Africa.

Image: The slave ship La Marie-Séraphique in a harbor in Haiti in 1773. Link.

1776

The United States declares its independence from England. Many of the values espoused in the new republic’s Declaration of Independence influence the thinking of slaves in Saint-Domingue, including the Declaration’s famous preamble, which reads:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

That same year economist Adam Smith writes that Saint-Domingue is “the most important of the sugar colonies of the West Indies."

August 9, 1777

King Louis XVI decrees the Police des Noirs, "a comprehensive legal code whose chilling goal had been brazenly stated in an early draft: 'In the end, the race of negroes will be extinguished in the kingdom."

The new code established "proto-concentration camps" to hold blacks and people of color in France. "The ideas was to circumvent the whole fifty-year tradition of freedom trials by refusing to allow blacks into France at all: the depots were on French soil but were explicitly extraterritorial, so that the freedom principle could not apply to them." (Reiss, p. 69)

April 12, 1779

France and Spain sign the Treaty of Aranjuez which officially recognizes French Saint-Domingue on the western third of Hispaniola.

September 16 - October 18, 1779

The Siege of Savannah is fought in Georgia as part of the battle for American independence. Fighters in the battle include "a battalion of free blacks and men of color from Saint-Domingue that included future French legislator and ex-slave Jean-Baptiste Belley, and future king of Haiti, Henri Christophe." (Reiss, p. 73)

Financial support of the American revolution caused a financial crisis in France in the late 1780s that had a destabilizing effect on King Louis XVI's rule (Reiss, p. 98).

1780s

By the early 1780s, Jérémie's economy is expanding more rapidly than any other area of Saint-Domingue due to a rise in global coffee prices and a simultaneous decrease in sugar prices. (Reiss, p. 41).

1784

France re-imposes the Code Noir from 1685 to reform certain planter abuses, this time issuing rules concerning slaves’ work hours, food rations, and quality of life. The Code restricts punishments and establishes minimal controls over the whites. The Code also legally obliges owners to provide slaves with small plots of land to grow food exclusively for their personal use. This issue of land rights is to become a central focus of the slaves’ demands during the revolution.

From 1784 to 1785, subsequent royal ordinances from France make it possible for slaves to legally denounce abuses of a master, overseer, or plantation manager. Few slaves benefit from these new rules, however, and in reality, the same system is still in place.

A Note on Saint-Domingue's Social Class System

"In the colonial period, the French imposed a three-tiered social structure. At the top of the social and political ladder was the white elite (grands blancs). At the bottom of the social structure were the black slaves (noirs), most of whom had been transported from Africa. Between the white elite and the slaves arose a third group, the freedmen (affranchis), most of whom were descended from unions of slaveowners and slaves. Some mulatto freedmen inherited land, became relatively wealthy, and owned slaves (perhaps as many as one-fourth of all slaves in Saint-Domingue belonged to affranchis). Nevertheless, racial codes kept the affranchis socially and politically inferior to the whites. Also between the white elite and the slaves were the poor whites (petits blancs), who considered themselves socially superior to the mulattoes, even if they sometimes found themselves economically inferior to them.

Of a population of 519,000 in 1791, 87 percent were slaves, 8 percent were whites, and 5 percent were freedmen. Because of harsh living and working conditions, many slaves died, and new slaves were imported. Thus, at the time of the slave rebellion of 1791, most slaves had been born in Africa rather than in Saint-Domingue."

- Richard A. Haggerty, ed. Haiti: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1989. Link.

Plantation and production were tied to the social class system. Sugar production held the greatest "promise of wealth and power" in Saint-Domingue. Tobacco, coffee, and indigo were "less labor-intensive crops [that] were the basis of most of the colony's smaller plantations or farms, some of them owned by free people of color (mulattos) and even by freed blacks." (Reiss, p. 32). "Coffee growers didn't get as rich as sugar planters did, but they also didn't need the same sort of capital to start up. Small hillside coffee plantations could be run with few slaves and at an entirely different pace of life." (Reiss, p. 35)

In the eighteenth century "Creole" had a different meaning than it does today, and signified white colonists who were born or at least significantly raised in the colony, rather than in Europe. To designate what we often mean by "Creoles" now, "people of mixed race"—part African and part European or Indian or Native American—the eighteenth-century French term was gens de couleur, literally "people of color." (Reiss, pp. 31-32)

With marriage and childbearing between slave owners, keep in mind that "given the basic master-slave relationship, all sex was a form of rape." (Reiss, p. 40)

The dynamics between the social classes were complex, including both "lavish mixed-race balls" and interracial police corps. "Eventually, the increasing role free people of color played in the fight against fugitive slaves would cause a permanent poisoning of relations between mulattos and blacks..." The culture and economic success of Saint-Domingue's free people of color ultimately led to a backlash, motivated in part by jealousy, that restricted dress, hairstyles, "'white' names," and more. "Along with this chilling backlash and the use of mulatto police and soldiers against fugitive slaves, the increasing number of mulatto slaveholders was also driving a violent wedge between the black and the mixed-race communities" by the late 1770s. (Reiss, pp. 42-44)

1788

The Monsieur Le Jeune case clearly demonstrated that the colony’s legal system still favored whites over blacks regardless of the revised Code Noir or evidence submitted in court. Le Jeune, a planter in the North, killed a number of his slaves after suspecting a poison conspiracy and tortured two other women with fire while interrogating them. Though Le Jeune threatened to kill his slaves if they tried to denounce him in court, fourteen of them registered an official complaint in Le Cap. Their allegations were confirmed by two magistrates of state, who went to the plantation to investigate. The two men found the interrogated women still in chains, their legs so badly burned they were already decomposing. One died soon after.

Despite this, white planters lined up to support Le Jeune. The governor and intendent wrote at the time that “It seems, in a word, that the security of the colony depends on the acquittal of Le Jeune.” The court was clearly complicit when it subsequently delivered a negative verdict, rendering the case null and void.

Image: 1728 Map of Le Cap. Link.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.