THE FRENCH REVOLUTION BEGINS: 1788-1790

Fall 1788

A petition is submitted to Saint-Domingue's Provincial Assembly requesting “political rights for free persons of color.” In November, another, similar petition is submitted by a white colonist, who is then “arrested at his residence, dragged through the streets, and brutally killed by a furious mob of petits blancs who cut off his head and paraded it through the town on a pike.” A respected elderly mulatto suspected of having a copy of the petition is shot and dragged through the streets.

A white colonist later writes in 1789, “What preoccupies us the most at this time are the menaces of a revolt . . . Our slaves have already held assemblies in one part of the colony with threats of wanting to destroy all the whites and to become masters of the colony.”

1789

Slaves in Martinique revolt, partly due to the influence of the French Revolution. Saint-Domingue is increasingly unstable as well: at the end of the year the colony experiences a devastating drought and marronage increases as slaves escape their plantations at higher rates. In reaction, whites become even more violent toward mulattoes, free blacks and white sympathizers.

A Note on Daily Life for Slaves

Tom Reiss' book, The Black Count, includes detailed accounts that help counter some of the overly-rosy narratives that plantation owners and managers wrote about slavery and quality of life on the plantations:

"The 'pearl of the West Indies' was a vast infernal factory where slaves regularly worked from sunup to past sundown in conditions rivaling the concentration camps and gulags of the twentieth century. One-third of all French slaves died after only a few years on the plantation. Violence and terror maintained order. The punishment for working too slowly or stealing a piece of sugar or sip of rum, not to mention for trying to escape, was limited only by the overseer's imagination. Gothic sadism became commonplace in the atmosphere of tropical mechanization: overseers interrupted whippings to pour burning wax—or boiling sugar of hot ashes and salt—onto the arms and shoulders and heads of recalcitrant workers. The cheapness of slave life brushed against the exorbitant value of the crop they produced. Even as the armies of slaves were underfed and dying of hunger, some were forced to wear bizarre tin-plate masks, in hundred-degree heat, to keep them from gaining the slightest nourishment from chewing the cane. The sugar planter counted on an average of ten to fifteen years' work from a slave before he was driven to death...[it was] a business model of systematically working slaves to death in order to replace them with newly bought captives."

— Reiss, Tom. The Black Count, p. 29

17-20 June 1789

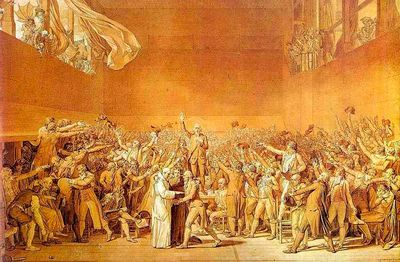

Tennis Court Oath

After being extensively lobbied, King Louis XVI is convinced to allow the doubling of the Third Estate. The Third Estate comprises about 96 percent of the French population who paid the bulk of taxes, and who demanded that its number of representatives ('deputies') double in order to equal the combined votes of nobles and clergy.

"The Estates-General got its name from the traditional division of France into three "estates": clergy, nobility, and commoners. [...] each had an equal number of 'deputies' to represent it. This meant that the clergy and nobility together could outvote anything that the rest, collectively known as 'the Third Estate,' wanted; the idea of proportional representation—or any meaningful voice for the people—was a sham."

However, it is too late, as "by this point a group of radical delegates had convinced a majority of commoners and liberal nobles that the entire archaic structure of the Estates-General should simply be thrown out and replaced by a national assembly in which there would be no estates and everyone would have an equal vote."

"Europe's most renowned absolute monarchy was suddenly the widest system of suffrage in the world" but a crisis is sparked when the "deputies arrived at the hall of their new National Assumbly to find that royal troops had blocked the gates and put up notices telling the deputies to return next week for a special 'royal session,' at which Louis planned to inform them personally that their actions were illegal and invalid. But instead of dispersing, the infuriated deputies marched to a nearby indoor tennis court, where they swore an oath not to leave until France had a constitution. (Reiss, p. 100)

The Third Estate declares itself “the nation, the true representatives of the people,” swearing “as a body, never to disperse.” Nearly all colonial deputies participate, “and in the general euphoria and enthusiasm” the Third Estate recognizes the principle of colonial representation and votes to seat six delegates from Saint-Domingue.

Following the Tennis Court Oath, mulattoes and free blacks in Saint-Domingue pursue representation and equal rights as free persons and property owners, but are blocked by white colonists. In the National Assembly, absentee planters prevent the reemergence of the “mulatto question” to avoid a debate that could grant these rights. Meanwhile in the colony free blacks are now richer, more numerous and more militant than in any of France's other colonies. Planters, fearful of giving up any control and increasingly divided amongst themselves, become more abusive, executing mulattoes whenever possible.

Image: The National Assembly taking the Tennis Court Oath (sketch by Jacques-Louis David, 1791). Link.

14 July 1789

The French Revolution begins with the fall of the Bastille. France’s political and social structures descend into chaos as the royal government collapses and violence breaks out.

26 August 1789

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens is adopted by the National Assembly. The Declaration’s articles include:

- Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good.

- The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.

- The free communication of ideas and opinions is one of the most precious of the rights of man. Every citizen may, accordingly, speak, write, and print with freedom, but shall be responsible for such abuses of this freedom as shall be defined by law.

- Since property is an inviolable and sacred right, no one shall be deprived thereof except where public necessity, legally determined, shall clearly demand it, and then only on condition that the owner shall have been previously and equitably indemnified.

Image: The 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens. Link.

5 October 1789

Louis XVI assents to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizens, saying that the rights are “granted to all men by natural justice.”

Meanwhile in Saint-Domingue during this period, the Colonial Assembly forms to combat actions the French National Assembly has taken on behalf of free blacks and mulattoes.

22 October 1789

The French National Assembly accepts a petition of rights for “free citizens of color” from Saint-Domingue.

8 March 1790

A new decree in France grants full legislative powers to the Colonial Assembly, giving the colony almost complete autonomy. The decree sidesteps "the mulatto issue," leaving it to the planters to interpret and declares that anyone attempting to undermine or to incite agitation against the interests of the colonists is guilty of crime against the nation.

Image: 1814 Map of Saint Domingue. St. Marc is located slightly north of Port-au-Prince on the coast. Link.

May 1790

News of the March 8 decree reaches Saint-Domingue. The Colonial Assembly in Saint Marc begins issuing radical decrees and reforms, pushing the colony further toward autonomy from France and creating conflict between the colony’s royalists and patriots. Saint Marc planters also vow that they will never grant political rights to mulattoes, a “bastard and degenerate race,” and expressly exclude them from the primary assemblies. Mulattoes continue to be frustrated in their attempts to secure their rights and a new Colonial Assembly is elected without a single mulatto or free black vote.

28 May 1790

The Colonial Assembly at Saint Marc issues one such decree declaring that its laws, like those made by the National Assembly in France, are subject only to the sanction of the king; that any National Assembly law regarding colonial affairs are subject to colonial veto; that the colony is from now on to be a “federative ally” and not a subject; and that the functions of the National Assembly colonial deputies are suspended.

Image: Free West Indian Creoles in Elegant Dress. Link.

12 October 1790

The French National Assembly dissolves the Colonial Assembly at Saint Marc. The governor of Saint-Domingue amasses troops to dissolve it by force. The colony is now divided between royalists and patriots; both groups court mulattoes’ support. The Colonial Assembly refuses to disband and issues a call to arms of all citizens. At last, outnumbered by the governor’s forces, the 85 assembly members realize they’re trapped. They manage to board a ship, the Léopard, and sail to France to plead their case to the National Assembly. There they attempt to reaffirm their right to legislate free persons of color.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.